Disturbing the Spirits

Do you believe in spirits and curses? While I consider myself a rational person, recent events perplexed me. On Juneteenth of this year I was poking around in the archives of the old Cheboygan newspapers researching a well-known crime in our past (more on this later). Instead, I learned about a different crime — a lynching that took place in 1883 in my very neighborhood, of a man named Till Warner. The alleged rape of 7-year old Nettie Lyons, and the lynching that followed, was widely reported at the time around the country. Why had I never heard about this lynching in all of my 45 years? As I researched more and walked the site of the lynching, a place familiar to me since childhood, I was determined to uncover more about this forgotten event.

My research led me to the book Lynching Beyond Dixie: American Violence Outside the South, edited by Michael Pfeifer, one of our country’s leading experts on the history of lynching. That study classified Till Warner as an African American, and thus the only Black man to be lynched in Northern Michigan. I wrote up my findings and published them here late on a Sunday afternoon.

Then things got weird. The next morning I found my cat — a healthy 10 year old — dead, his head hanging lifelessly from his favorite chair. Meanwhile my 5 year old daughter, who used to enjoy playing with me in the field where the lynching took place, stopped eating, prompting multiple trips to her doctor. (She’s better now.)

Coincidence? Yeah, probably — I’m a rational person. But there seemed to be more to the story. The spirits were not appeased.

Like a pebble in one’s shoe, there was one big detail about the Till Warner story that continued to bother me and kept me from moving on: what role did racism play in the lynching? The two local newspapers of the time — the Cheboygan Democrat and the Northern Tribune — made no mention of Warner’s race in their reports. But the Grayling Avalanche, the New York Times and some other papers around the country identified the victim as a “negro”. Several possibilities suggested themselves:

(1) Perhaps the Cheboygan newspapers did not report Warner’s race because it was assumed.

(2) Perhaps the Cheboygan newspapers wanted to cover up the race of the victim, out of concern for how the town would be perceived by outsiders.

(3) Perhaps the national newspapers assumed that Warner was a negro, to fit an awful news script that was already commonplace: that black men were raping white women, and that white people were taking measures to defend themselves.

So I kept researching and I eventually did learn more about the victim at the center of this story. What I learned is quite significant, and changes the meaning of this episode in our town’s history. But before I reveal this information to you, think back a minute. When you first read that a black man was lynched in our town, what did you feel?

Did this information shock you — why exactly? Did it confirm what you had always thought about Cheboygan? Did you think this story made our town more racist than any other town in America? Did you find yourself doubting the veracity or relevance of the story — and if so, why?

While you reflect on your reaction, I’ll share mine: learning about this story made me feel very ashamed. Shame that, when I had returned to Cheboygan from the South, I had ever thought I was somehow escaping the history of American racism. And it made me think about this: maybe the comfort that I felt on returning to my hometown — at a deep level — had to do with retreating into a (mostly) white space, where I would not be forced to confront my own racist habits of mind. It made me question the comfort of home, where I had always felt that I could be most myself. Cheboygan seemed to be peripheral to the story of American racism — and yet a lynching had once taken place beneath my very feet. Clearly the spirits have a dark sense of humor!

Who was Till Warner?

The newspaper accounts of the victim provided two clues: (1) Tillock Comstock Warner was born on August 16, 1850 in East Saginaw and later moved to Alpena as a child, and (2) his father’s name was Stephen and lived in Alpena. From those pieces of information I was able to conduct a search of public documents to learn more about Till. The first document is the 1860 Census form for Alpena County.

Stephen Warner, aged 40, is recorded as a Fisherman born in New York state. His son Tillerick, aged 10 years old, is recorded as the middle of 5 children. Stephen Warner appears again in the 1870 Census in Alpena, recorded now as the father of 3 more children, but Till (now aged 20) had apparently left the household. In both censuses the family was recorded as “White”.

The various newspaper accounts describe Till Warner as a “tramp” and a “rover”, working in fishing for his father when he was younger. Later, he worked the logging camps of the Saginaw Valley and Thunder Bay regions in the winter, and as a sailor on the Great Lakes in the summer season (work that brought him to the port of Cheboygan). The fact that he does not appear on any census forms after 1860 suggests a vagabond life.

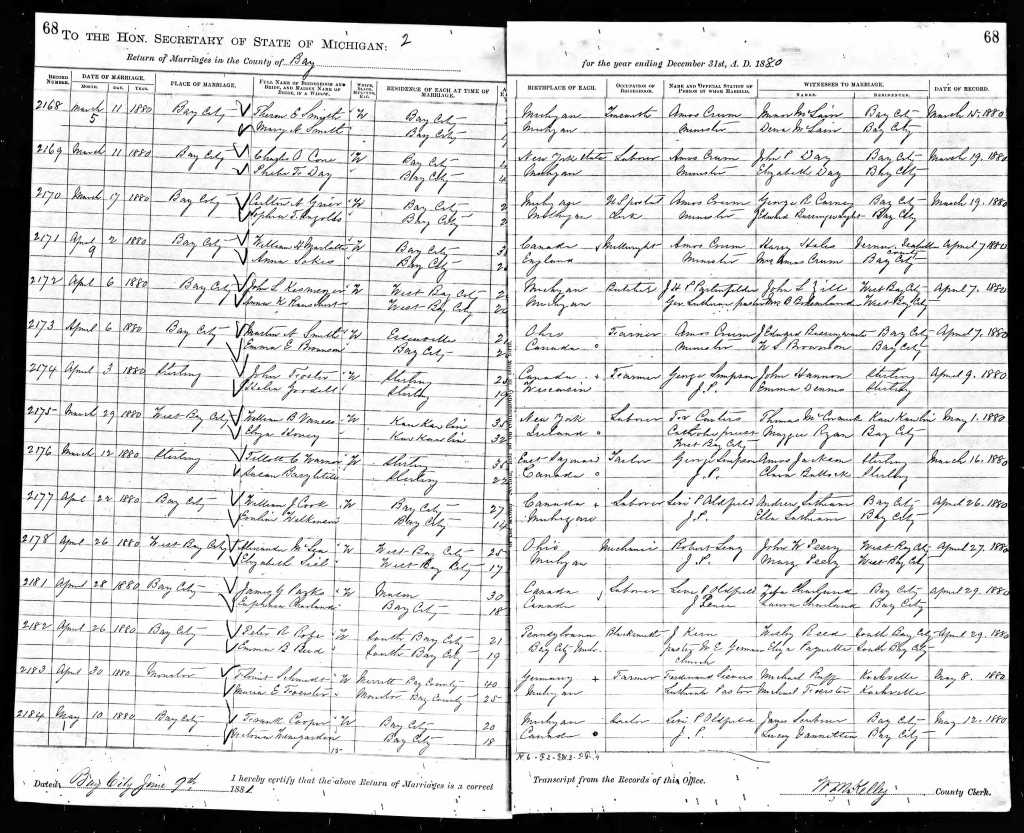

The only public record I could find of the adult Till was a marriage record from March 16, 1880 in Sterling, a tiny village in the north of Bay County. Both he and his bride, a Canadian woman, are recorded as “White”.

From the available evidence, it appears that Till Warner was regarded as a white man his entire life. But we also learn that he apparently came from a hard background, the middle of at least 8 children, born into a family and community of fishermen. He did hard physical labor his whole life and does not seem to have had a settled home. By his own admission he drank too much, and caused himself much harm as a result.

Although I consulted over a dozen newspapers, I still have not been able to determine which one was responsible for transforming Till Warner into a “negro”. But it’s not hard to see how it happened, and it may be that several newspapers added the racial background independently of each other. News reports of the time were filled with stories of lynchings — many, though not all of them, black men. Most of these lynchings were explained as retaliation for a sexual assault that crossed the color line. As it happens, Warner’s murder took place on the very same day as the lynching of a black man in Alabama. The New York Times reported both episodes under a single header “Brutal Negroes Lynched.” You read that right — the spin on the story is that the “negroes” were the brutal ones, while the white people “took the law into their own hands.”

A case of misidentification?

In my first report on Till Warner I described a disturbing, but sadly familiar story of white mob violence committed against an African American: a racial terror lynching. But from what I have learned since then, Till Warner identified as white. That makes the mystery deeper: why would this man have been lynched? Lynchings of whites did take place around the country — they also occurred in Menominee in 1881 and in Grayling in 1888, but otherwise they were not common in Michigan.

Let’s consider this hypothesis: Is it possible that the suspect in the Nettie Lyons case was believed by the citizens of Cheboygan to be a black man? Is it possible that Till Warner himself was thought to be a black man by the assembled mob? Perhaps, on examining his dead body the following morning, it was determined that he was in fact white, and the local newspapers made no mention of his race. Perhaps the local newspapers deliberately avoided identifying his race, in an effort to conceal this racial misidentification. That may sound absurd, but mistaken identification did happen. Consider these two stories of near-lynchings from 19th-century Michigan.

First, here is an account of the 1863 race riot in Detroit, in which white Detroiters rampaged and burned the city’s predominantly black neighborhood. Note the person and the incident that touched a white nerve:

As in other Northern cities, many whites resented the government’s military draft [during the Civil War] and the blacks, largely from the South, who had arrived in town. The local Democratic newspaper, the Detroit Free Press, frequently ran articles accusing African Americans of causing various problems that mainly affected the city’s working-class whites. The newspaper promoted the idea that freedmen leaving the South would take jobs from white men which in turn contributed to heightened racial tension in the city.

Tensions in Detroit finally boiled over during the trial of William Faulkner, a mixed-race man accused of molesting two girls, one of whom was white. Even though Faulkner identified as a “Spanish-Indian” and had previously voted (at the time, only white men could vote), the Free Press and other newspapers labeled him a black man. As far as the white public was concerned, Faulkner was black and had raped a white girl.

When Faulkner was escorted after the courtroom after the first day of his trial, a large crowd of whites harassed him and threw stones. The next day, March 6, an even larger mob assembled outside the courthouse. Faulkner was convicted and sentenced to life in prison, but the agitated crowd still attacked him as he was transported back to jail. The Detroit Provost Guard, charged with his protection, fired blanks in an attempt to disperse the crowd. When the mob remained, they fired live ammunition, killing a white bystander named Charles Langer.

DETROIT RACE RIOT (1863), Adam Rozen-Wheeler

Fast forward to 1883, the year of Nettie Lyons’ assault in Cheboygan. As I have been reading through newspapers of the period, I have found that they are filled with accounts of other lynchings. Citizens in Cheboygan (and other towns in Michigan, for that matter) may have had very little to no experience with black people, but they were exposed to a steady stream of newspaper reports, detailing lynchings. Reports of black men assaulting white women were a very common media script, as the Detroit riot makes clear.

Is it possible that these news reports conditioned the people of Cheboygan to expect that a rape suspect would be black? Here is the second story to consider, another case of mistaken identity from only a few weeks after the Cheboygan lynching:

I’m sure you, too, noticed what happened there, because the racism is not very subtle. Hundreds of people were ready to lynch the Schermerhorn kid when they thought he was African American — but when it turned out that he was a German kid in black face, then, well…due process.

The residents of Cheboygan were fed a steady diet of “negro crimes” in their newspapers, but were they accustomed to seeing black people in their daily lives? Probably not, and for that reason it is possible that Warner was identified as a black man, even though he regarded himself as white. It still happens, because I’ve seen something like this in my own life. One summer I invited a Korean friend to visit my home and we road-tripped around Northern Michigan. As we left a village store, a man started speaking to him in Spanish — assuming that he was Mexican. It was a harmless mistake, made by someone who probably had not met a Korean person before.

While it is possible that Till was misidentified, to pursue this explanation further would be to enter the genre of historical fiction — a type of writing that, when based in informed speculation, can get at the heart of historical truths in a way like no other, if it is done well. But that is not my calling.

A story of race — and class

Till Warner identified as white, and he was the victim of a lynching: there are conclusions to be drawn from these two basic facts. They are different than I expected when I first started researching the lynching. And that’s not a bad thing.

First, this remains a story of American racism. All Americans at this time, not just the residents of Cheboygan, were socially conditioned by a decades-old racist script: the fear that black men were a sexual threat to white women. That script called upon white townspeople to act together to take retribution, in an act that affirmed their collective manliness. Here, for example, is what the Romeo Observer wrote about the Cheboygan lynching:

The people of Cheboygan are law-abiding – they were so before they hung the wretch Warner, and they will doubtless remain so to the end of their days. We consider it creditable to their manhood, that in the presence of the hideous and damnable crime, committed on a weak and helpless child, they were urged by their feelings even to the meting out of the punishment the wretch so eminently deserved.

The victims of 19th-century lynchings included Blacks, Native Americans, Whites, Chinese, Japanese — but there was no such diversity in the lynching posses. They were all perpetrated by white men who used violence to police the boundaries of their community. The essentially racist nature of American lynching is clear in the Till Warner case by the very fact that some newspapers chose to falsely identify him as a “negro.” Whether intentionally or not, the victim was made to fit the racist script.

In Till’s fate we also see the way that race and class are intertwined in American life. Here was a man with no fixed address, who sold his labor on the market, passing through a town where he apparently had no friends. With no advocate in the community, he was vulnerable to the prejudices of the frightened townspeople. Would the lynching have taken place if he lived in Cheboygan? Or if he were a person of wealth and influence, known to other members of the community? Almost certainly not. The people of Cheboygan regarded Till as suspicious and undeserving of due process precisely because of the kind of person that he was.

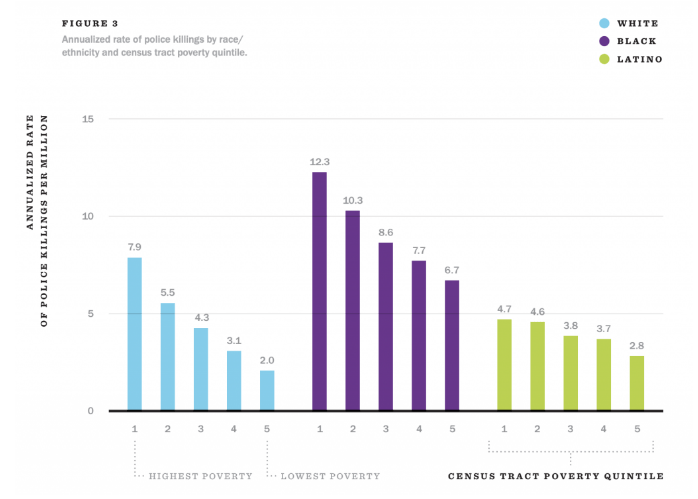

The long history of American policing has its origins in the control of African Americans and their treatment as a criminal class. But it is a system that has also disproportionately criminalized white Americans in the lowest economic classes. A recent paper analyzing the last 5 years of police killings demonstrates that African Americans of all economic classes are killed at hugely disproportionate rates — as are white Americans in the lowest economic class:

The demands to end policing as we know it have the potential to liberate not only African Americans from the terror of state violence, but many poor whites as well. Police killings in our country far exceed the rate of police killings in other countries. The vision of what will replace our current system is still taking shape. Whether we will achieve mutual liberation depends on building a true multi-racial working-class movement to attack the problem directly.

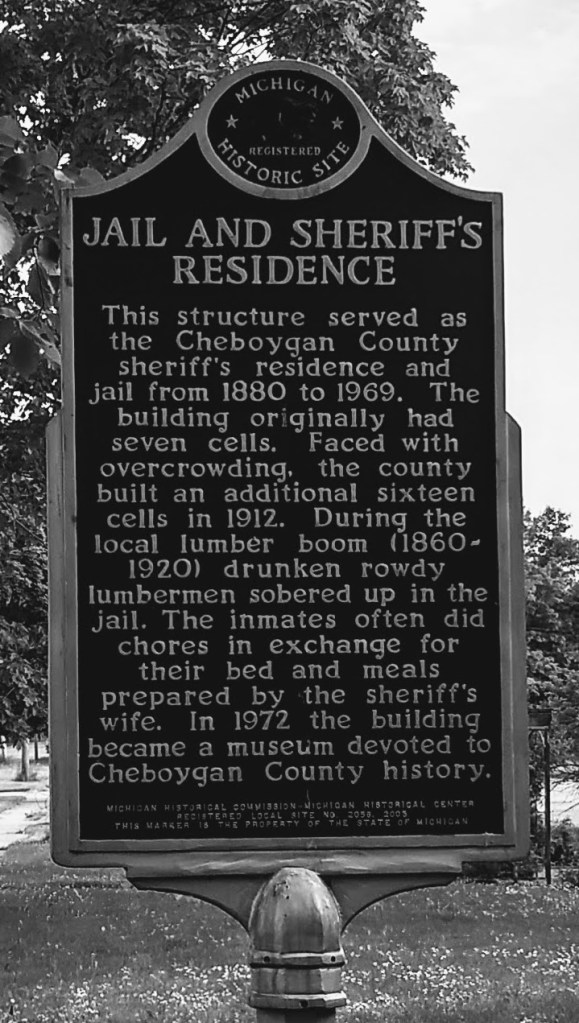

Today the historical marker in front of the old Cheboygan jail conveys a folksy image of the past, of a place straight out of Barney Fife’s Mayberry. A pleasing fiction, in other words. But here’s the reality: on one June day, the doors of that newly built jail opened at the command of a white mob, and a man was lynched within sight of the courthouse. Over 100 years later the methods have changed, but the terror continues.

Great research and coverage of racism and tying to ongoing police violence against MOSTLY blacks. Love your blog –always a good read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reading, Karen!

LikeLiked by 1 person