[I began researching this story on Juneteenth, 2020. Since then I’ve learned new information and the story is, if anything, stranger and the implications for today deeper. I will provide an update in Part 2.]

When I moved away from Cheboygan at age 18, I began the long process of learning about the true history of racial oppression in this country. While I was exposed to some of this history in high school, it seemed very remote to me, growing up in a mostly white town in Northern Michigan. Racial oppression of African Americans seemed to happen out there, especially way down South. It was a history that I accessed through movies and occasionally an assigned book, like The Invisible Man.

But living in South Chicago, West Philly, Los Angeles, and North Carolina was a very different kind of education. It was obvious that racism shaped the lived experience of these places. The cityscapes were defined by the history of red-lining, by militarized police forces, fortress architecture, food deserts, underfunded public transportation networks, and capital flight from minority neighborhoods.

In North Carolina I was confronted with the continuing legacy of slavery more immediately than anywhere else I lived. I worked at a public university that was built with slave labor, whose Memorial Hall was so named because it memorialized the names of Confederate officers, and that — until this year — even had a statue of a Confederate soldier presiding over its idyllic academic green. Further out from campus, the landscape became a sprawl of suburban developments and postmodern office parks. But in between the new developments were relics of the former slave economy, as well as places marked by lynchings, violence — and resistance. Every day I went to work I felt the weight of the past in the present.

There were many reasons I left North Carolina — the suffocating heat, poisonous snakes and giant spiders, homesickness — and I very much looked forward to moving north of the Mason-Dixon Line permanently. I looked forward to living in a town with a giant Union cannon, rather than a Confederate statue, proudly on display.

What an idiot. Because it turns out that the people of my hometown, in addition to swindling the Native population of their land and impoverishing them, also turned out in their hundreds to lynch an African American man in 1883. It’s an event that was luridly described by our hometown papers at the time, and carried by newspapers all across this country. Never once was this event mentioned when I was growing up. And yet it all took place a few blocks from the house where I grew up. The haunted relics of that story are still here in my neighborhood, for those who go looking.

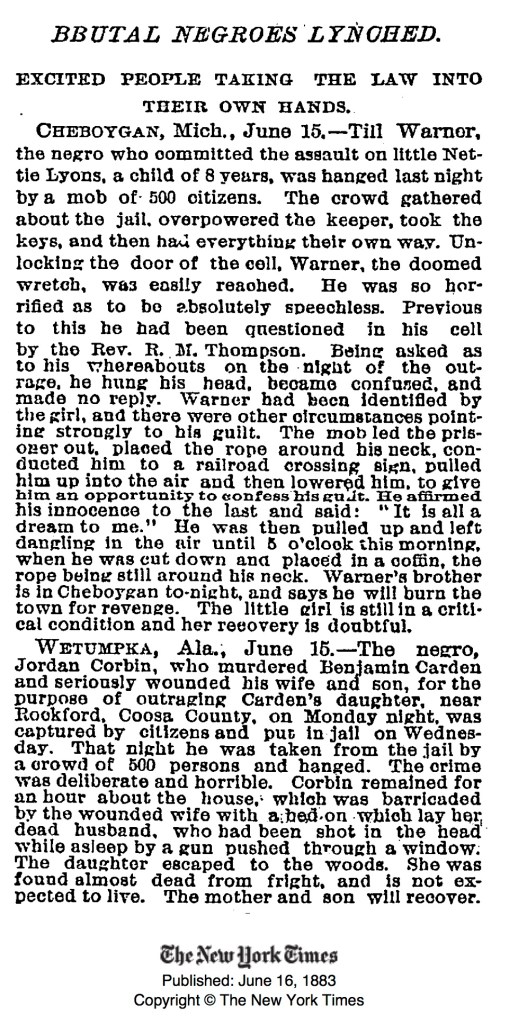

I stumbled upon the story recently when combing through Cheboygan’s early newspapers, The Northern Tribune and The Cheboygan Democrat. (Thanks go to our local public library for digitizing our town’s early newspapers, which you can access here.) The story of Nettie Lyons’ alleged rape, the quick arrest of Till Warner, and his public lynching by a group of 600 men late on the night of June 14, 1883, is told in the most sensational detail.

Nettie Lyons was a local 7-year old girl who went missing as she walked from home to meet her father at work. When she failed to show up by bedtime that Tuesday evening June 12, her father and a family friend searched the town. In the early hours of Wednesday morning they finally found her, bruised and asleep, in the swampy woods near the train depot. This is a spot I know well — it’s where my friends and I used to race our BMX bikes as kids, and where I now like to walk with my family. When my daughter became interested in ghost stories, I used to make up ridiculous stories about the haunted woods at that very spot.

Although the word rape is never used in the local newspaper reports, it is the clear impression left by the reporters, who describe her torn clothes, bruised body and “gaping stab wound”. The language is so florid and emotional, however, that it’s not clear what Nettie really suffered. As the reporter with the Democrat noted “her mind is clear, but is so weak that she can only tell her story in a disconnected way…” What is clear is that the people in town understood her to be the victim of rape and attempted murder, and there was one man who became the focus of their rage: Tillott Comstock Warner.

Till Warner, as he was called, was born in East Saginaw on August 16, 1850. At some point he made his way north, taking up residence in Alpena, but moved frequently as he worked on ships and in the lumber camps. He was only passing through Cheboygan that June, not even spending the night, and was quickly apprehended on the outskirts of Mackinaw City by the search parties that went looking for him. He was brought to the newly built County Jail that Wednesday afternoon, and a throng of over 1,000 people came out to learn about Nettie and the man who was alleged to have raped her.

Huge crowds continued to form around the jail the next day, trading rumors about what had happened. It was quickly decided to take action before Till Warner could be brought to trial. Here is the Northern Tribune’s reporter: “Beer and whisky had nothing to say in the matter, but serious men, thinking of the supreme importance of protecting the virtue and safety of mother, wife and daughter, and also of preserving the majesty of the law, were carried as it were to an irresistible conclusion that it was their solemn duty and obligation to see the guilty suffer death.”

Later that Thursday night a group of masked men numbering in their hundreds forced their way into the jail, and even more bystanders cheered them on — “the air rung with music made by two thousand hands clapping generous applause.” Warner was taken out of the cell and led down Court street a couple of blocks to the railroad crossing. Again, it is easy to identify the location today, although the train tracks have been removed and replaced with a recreational rail trail.

From the beginning Till Warner proclaimed his innocence — to the authorities, to the reporter who interviewed him in his jail cell, and in his final words before he was hung from the railroad crossing sign. As the men prepared to hang him, Till Warner is reported to have said “Gentlemen, I am going to die, and all I have to say is, I am an innocent man. I work at lumbering in the winter, and sail in the summer. I spend all my money for whisky. I never did any harm to any man, or any one but myself…The only prayer I have to make is that God will have mercy on your souls, this is all I have to say. I am innocent, and when you have hung me, probably you will find the man.”

And some believed him at the time. Even Joe Littlefield, the man who had apprehended Till Warner and brought him to jail, told the Democrat’s reporter that he believed an innocent man had been killed. But despite the numerous witnesses, no one — not even the verbose local reporters — could name the individuals responsible for the hanging. Somehow, in our small town, their identities remained a “mystery” and they went unpunished.

What else do we know about Till Warner? The local reporters do not mention his race, even though the Northern Tribune gave a physical description of his size (5’6″). But other newspapers across the country made his race one of the lead details in their reporting — he is identified as a “negro” in the local Crawford Avalanche (Grayling) and in the New York Times‘ write up of the event. Till Warner’s race may explain the irrational anger and fear that took hold of the Cheboygan people — lynching in Northern Michigan was rare, both before and after this event.

Contemporaneous newspaper reports make clear that the events in Cheboygan were part of a well-established pattern: across the country, white vigilantes were taking the law into their own hands, out of an irrational fear that African American men were going to rape white women and kill their white husbands and fathers. And it all took place with the tacit agreement of “legal” authorities. This script has played out for generations and conditions the way we think about black men and policing.

More than 4,000 African Americans were lynched between 1877 and 1950. This terror reached many corners of the US, including right here in Northern Michigan. The murder of Till Warner is the only known lynching of an African American in Northern Michigan. In 1883, hundreds of people in Cheboygan participated in the extra-judicial killing of this man. Today, we would like to consider ourselves more humane than our ancestors, but amazingly — as of June 19, 2020 — our US Senate still cannot agree on passing the Emmet Till Antilynching Act (Want to know who’s to blame? Say his name: Rand Paul). And we still allow our tax dollars to support a policing apparatus that commits extra-judicial killings by the thousands.

Dear reader, there is no space in our country that is outside racism, including small town Northern Michigan. The history of racism is present here, too, if we take the time to look. It is present on our TVs, in our conversations, and in the political choices we make.

Say his name: Till Warner.

Say his name: Emmet Till.

Say his name: George Floyd.

I knew about the alleged rape, I knew about the hanging—but until you exposed that the victim of the hanging was anyone other than I white man–I had no idea. thanks for sharing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am a Northern Mi. local. Never learned about this in school or from parents or relatives. I wonder why? So sad.

LikeLiked by 1 person

wow!! 9From one-room schoolhouse to…one-room schoolhouse

LikeLike