[The following is a slightly expanded version of my guest editorial in the Cheboygan Daily Tribune, from April 19, 2019. Click here for the original article.]

This past December caseworkers from the Department of Health and Human Services attended a public office hour with Lee Chatfield, to sound alarm bells about major problems in the department. Their warning made an impact on me and several other concerned citizens who were in attendance. So we decided to investigate further, by contacting DHHS staff and clients, service providers, and union representatives from across our region. What we learned was shocking. According to the department’s own data, people in need were encountering average phone wait times of 1-2 hours just to speak with a DHHS worker, and months-long delays in receiving determination letters; meanwhile front-line staff were frustrated with a new program that made it extremely difficult to provide help to their clients. The bottom line: families seeking heat, food, and medical assistance were not receiving the service they deserve as taxpayers.

Several factors combined this winter to cause trouble at the DHHS, but chief among them was the implementation of a new program: Universal Caseloads (UCL). Whereas previously a client was assigned a specific caseworker who would guide them through the process of applying for assistance and track their progress, under the new program clients are connected with a different worker each time they call an office.

As a further part of UCL implementation, county offices have been reorganized within much larger regional units. Cheboygan County, for instance, is now part of a 10-county DHHS regional grouping. As a result, someone from Cheboygan calling for assistance may be connected randomly with a DHHS worker in Traverse City one day, or Manistee on another day.

While the department initially touted UCL as a way to deliver more efficient service, the opposite has resulted. This is partly because, in the “team-based” approach of UCL, there is little continuity when a case is handed off from one worker to another: each worker comes to a given case with little understanding of the client’s history or context. Furthermore, because of the large regional units, workers may not be familiar with the service providers in the area where their clients live. These problems have been compounded by the large volume of phone calls now received at DHHS offices, from clients who are trying to confirm the status of their eligibility. As we have learned, DHHS workers have found it nearly impossible to keep up with the incoming phone calls, while also processing all of the applications received.

UCL was first implemented in May 2018 in rural areas of our state, with the expectation that it would roll out to all counties in Michigan. But when it became clear that the situation had reached a crisis point in regions with UCL, in January the DHHS halted any further implementation of the program to metropolitan areas. Thus Northern Michigan has been bearing the brunt of this poorly designed program, a failed experiment in “efficiency”.

What we learned troubled my colleagues and me, and was hard to ignore. In response we formed the Center for Change, a group of citizens from Northern Michigan and the Eastern UP who seek to advocate for solutions to regional problems. Since December we have been lobbying our state representatives, our governor and the new DHHS director, Robert Gordon, to make immediate improvements to the department – because lives are at risk.

We are finally seeing improvements at the department, under the new DHHS director. Gordon has responded to critics by making the department’s data on UCL publicly available on the MDHHS website. He has promised to listen to the public and staff, and will make a decision about the future of the program in the coming months. In the meantime he has directed 85 workers from non-UCL counties (such as Wayne) to work on the case backlog in UCL regions, such as Northern Michigan.

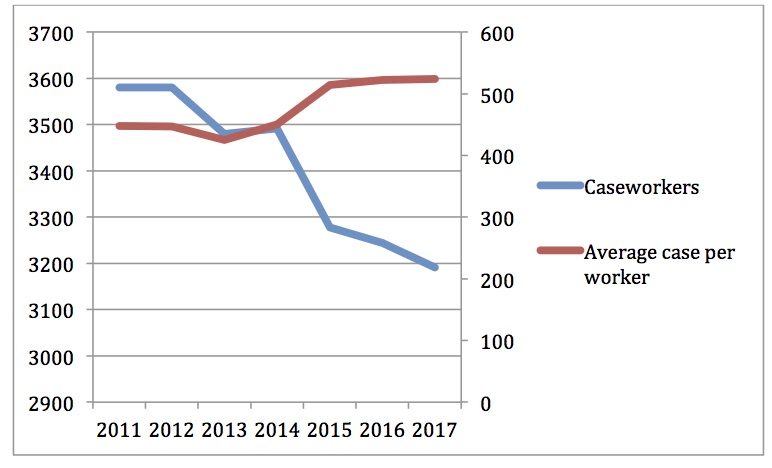

But shifting workers from one county to another is a temporary fix, and does not get at the root of the problem: the department needs to hire more caseworkers. State funding for the department (controlled by the legislature) is still below its 2008 level, even though the percentage of Michigan residents receiving DHHS assistance grew from 18.1% in 2008, to 26.4% in 2017. Poor funding has had the results you would expect. Between 2011 and 2017 the number of caseworkers at DHHS declined from 3,580 to 3,191, and the average number of cases per caseworker increased from 448 to 524. The reduction in force that followed Snyder’s merger of the Department of Community Health and Department of Human Services, in 2015, marks the beginning of this dangerous trend. UCL (“team-based” social work) was implemented to deal with the reality of fewer caseworkers.

What we are now witnessing is a department under great stress, struggling to deliver on its important mission of helping people in need. What will happen when our state experiences another economic downturn?

Meanwhile, Governor Whitmer has requested $10 million in her budget in order to train current DHHS staff on the coming regulations resulting from the Medicaid work requirements, implemented by former Gov. Snyder and the Republican legislature. Although a small amount of money in the context of the overall budget, it is the equivalent of approximately 170 caseworker salaries. There is no doubt that such a number would have a big impact on DHHS responsiveness; after all, it took only 85 additional workers to reduce the backlog in UCL counties dramatically, from January to April.

County Democratic parties from across the Eastern UP and Northern Michigan have joined our advocacy, requesting that Gov. Whitmer and Robert Gordon increase the number of caseworkers at the department, among other changes. But this issue should not be a partisan one. We need more Republicans to follow the lead of Ed McBroom, the Republican state senator who represents the UP. He has publicly called on the department to scrap UCL and return to smaller regional units, with caseworkers responsible for fewer cases. With Republicans in control of the legislature, they have the opportunity to direct the necessary funds to the department, so it can hire more caseworkers.

As a former DHHS recipient himself, Sen. McBroom knows the importance of the department’s mission, and the value of a good caseworker. He may also understand a more fundamental truth: few people experience good luck their whole lives. When our luck turns, when the economy sours, we look to our social safety net – funded by our taxes – to get us back on our feet. We look to the helping hand of a caseworker, a neighbor who has chosen to make helping people their profession.